by admin | Aug 2, 2015 | Uncategorized

Weekly Breaking Research Updates

Scientific breakthroughs happen every day! In an effort to help our patients stay up to speed on the most cutting edge treatment options available for them, our scientists monitor current research and publish weekly research updates. The title of each article below is a link to the full study report. If you’d like to make an appointment with Dr. Hanna to discuss your treatment options, please contact us.

Ketamine

Gender and estrous cycle influences on behavioral and neurochemical alterations in adult rats neonatally administered ketamine

VCM Borella, MV Seeman, RC Cordeiro… – Developmental …, 2015

Abstract Neonatal NMDA receptor blockade in rodents triggers schizophrenia-like

alterations during adult life. Schizophrenia is influenced by gender in age of onset,

premorbid functioning and course. Estrogen, the hormone potentially driving the gender …

Hypothalamic, thalamic and hippocampal lesions in the mouse MCAO model: potential involvement of deep cerebral arteries?

M El Amki, T Clavier, N Perzo, R Bernard, PO Guichet… – Journal of Neuroscience …, 2015

… Anesthetic methods in rodent models of cerebral ischemia impact the infarct volume. In

experimental models developed in rodents, the most used anesthetics are the volatile ones such

as isoflurane or halothane and intraperitoneal (ip) ketamine or barbiturates. …

Targeting the CD80/CD86 costimulatory pathway with CTLA4‐Ig directs microglia toward a repair phenotype and promotes axonal outgrowth

A Louveau, V Nerrière‐Daguin, B Vanhove… – Glia, 2015

… Male LEWIS 1A rats were anesthetized by intramuscular injection of 2% Rompun and 50mg/mL

ketamine (1.6 mL/kg) (PanPharma). … Twenty-eight days after transplantation, grafted-male Lewis

1A rats were deeply anesthetized with Rompun-ketamine (1:4) at 1 mg/kg (ip). …

[PDF] Anti-nociceptive effects of taurine and caffeine in sciatic nerve ligated wistar rats: involvement of autonomic receptors

W Abdulmajeed, BV Owoyele – Journal of African Association of Physiological …, 2015

… (St. Louis MO, USA) while propranolol and prazosin were products of Namco

Chemicals, Amritsr, India. Normal saline and ketamine were purchased from Momrota

pharmacy, opposite University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital’s gate. …

Two Cellular Hypotheses Explaining Ketamine’s Antidepressant Actions: Direct Inhibition and Disinhibition

OH Miller, JT Moran, BJ Hall – Neuropharmacology, 2015

Abstract A single, low dose of ketamine has antidepressant actions in depressed patients

and in patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). Unlike classic antidepressants,

which regulate monoamine neurotransmitter systems, ketamine is an antagonist of the N- …

Effect of Piperine on Liver Function of CF-1 albino Mice.

JR Peela, SD Kolla, F Elshaari, F Elshaari, H El Awamy… – Infectious disorders drug …, 2015

… with high fat diet. These mice were anaesthetized with ketamine and halothane and

blood was drawn from each mouse before the study and after three weeks by

cardiocentesis. Serum transaminases (alanine aminotransferase …

[PDF] Correlation between anti-HBs and immunostimulatory cytokines following hepatitis B vaccination in mice

OU Peter, PO OKONKWO, OO John, A Dorathy – 2015

… AM daily. All mice were acclimatized for two weeks. Diazepam injection (Valium,

Roche, USA), and ketamine injection (Ketalar, Popular Pharmaceuticals, Bangladesh)

were procured from Pax Pharmacy, Onitsha. Hepatitis B …

Phosphodiesterase‐4D: an enzyme to remember

R Ricciarelli, E Fedele – British Journal of Pharmacology, 2015

… enzyme isoform is localized in brain regions associated with emesis (eg area postrema and

nucleus of the solitary tract; Cherry and Davis, 1999; Lamontagne et al, 2001; Mori et al, 2010)

and its deletion in transgenic mice reduced the xylazine/ketamine-induced anaesthesia, a …

The effects of tacrolimus on the activity and expression of tissue factor in the rat ovary with ischemia–reperfusion induced injury

UV Ustundag, S Sahin, K Ak, I Keskin… – Reproductive Biology, 2015

… the ovaries. The rats were anesthetized with a combination of ketamine hydrochloride

(60 mg/kg ip.) and xylazine (5 mg/kg ip.). Supplementary injections of ketamine

hydrochloride were given when needed. After anesthesia …

Novel Rat Model for Neurocysticercosis Using Taenia solium

MR Verastegui, A Mejia, T Clark, CM Gavidia… – The American Journal of …, 2015

… Before intracranial inoculation, the rats were anesthetized with 70 mg/kg of ketamine plus

11 mg/kg of xylazine. … Animals were euthanized after being anesthetized with a mixture of

100 mg/kg of ketamine, 10 mg/kg of xylazine, and 3 mg/kg of tramadol. …

Photo of the Day: Low-dose Ketamine Infusions

A Katz – Emergency Medicine News, 2015

Wolters Kluwer Health may email you for journal alerts and information, but is committed to maintaining

your privacy and will not share your personal information without your express consent. For more

information, please refer to our Privacy Policy. … This blog serves as a bulletin board for …

[HTML] Impact of Anesthesia Protocols on In Vivo Bioluminescent Bacteria Imaging Results

T Chuzel, V Sanchez, M Vandamme, S Martin, O Flety… – PLOS ONE, 2015

… S. aureus Xen36 strain. Bioluminescence imaging was performed on mice

anesthetized by either ketamine/xylazine (with or without oxygen supplementation),

or isoflurane carried with air or oxygen. Total flux emission was …

Sedative and Anxiolytic Agents

SI Ganzberg, S Wilson – Oral Sedation for Dental Procedures in Children, 2015

… The salient fea- tures of nitrous oxide, chloral hydrate, meperidine, midazolam, antihista- mines,

and ketamine are discussed in relation to sedating children for dental procedures. … Studies

using ketamine administered orally have resulted in mixed results. …

[HTML] Fractionated Radiation Exposure of Rat Spinal Cords Leads to Latent Neuro-Inflammation in Brain, Cognitive Deficits, and Alterations in Apurinic Endonuclease 1

MAS Kumar, M Peluso, P Chaudhary, J Dhawan… – PLOS ONE, 2015

… Ethics Statement. All exposures to radiation were done under ip anesthesia of xylazine/ ketamine

mixture- 4.3–5 ml per rat (male, Wistar strain) for an average weight of 540–600 gms (80 mg/kg

body weight of ketamine and 8 mg/ kg body weight of xylazine in PBS). …

Combinations of dexmedetomidine and alfaxalone with butorphanol in cats: application of an innovative stepwise optimisation method to identify optimal clinical doses …

C Adami, T Imboden, AE Giovannini, C Spadavecchia – Journal of Feline Medicine …, 2015

… anaesthesia. Commonly used protocols often include an a 2 -adrenoreceptor agonist

to produce reliable sedation, an opioid derivative to provide some analgesia, and

ketamine owing to its anaesthetic and analgesic effects. …

[HTML] Development of Animal Models of Local Retinal DegenerationAnimal Models of Local Retinal Degeneration

H Lorach, J Kung, C Beier, Y Mandel, R Dalal, P Huie… – … Ophthalmology & Visual …, 2015

… Animal facility. For surgeries, animals (P35–P50) were anesthetized with ketamine

(75 mg/kg) and Xylazine (5 mg/kg), delivered by intramuscular injection. Subretinal

implantations were performed as previously described. 31 …

[HTML] Following specific podocyte injury captopril protects against progressive long term renal damage

YS Zhou, IA Ihmoda, RG Phelps, COS Bellamy… – F1000Research, 2015

… VD DOM02, made by Orion Pharma, supplied by Henry Schein Medical) and 100mg/ml

ketamine (Vetalar) (Ref. … Terminal blood samples were collected at week 8 from intraperitoneally

anaesthetised animals (injected with medetomidine and ketamine). …

Clinical Sedation Regimens

S Wilson – Oral Sedation for Dental Procedures in Children, 2015

Page 74. Clinical Sedation Regimens Stephen Wilson S. Wilson, DMD, MA, PhD

Division of Pediatric Dentistry, Department of Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Avenue, Cincinnati, OH 45229 …

Electrocardiogram reference intervals for clinically normal wild-born chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)

R Atencia, L Revuelta, JD Somauroo, RE Shave – American Journal of Veterinary …, 2015

… Immediately before the examination procedures, body weight was estimated.

Chimpanzees were anesthetized by administration of a combination of ketamine

hydrochloride a (5 mg/kg) and medetomidine b (50 μg/kg). Anesthetic …

Deep Sedation and GA

SI Ganzberg – Oral Sedation for Dental Procedures in Children, 2015

… When an anesthesia machine capable of delivering sevoflurane is not available, as is typical

is most dental offices,“induction” is most commonly provided with an intramuscular injection of

ketamine and midazolam with or without an anticholinergic, ie, such as glycopyr- rolate or …

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA)

In-utero radiofrequency ablation in fetal piglets: lessons learned

OO Olutoye, AN Gay, F Sheikh, AC Akinkuotu… – Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 2015

Methods 90 day gestation Yorkshire piglets (term 115 days) were subjected to RFA of the

chest and abdominal viscera under various temperatures and wattages. The extent of tissue

damage was determined by NADPH diaphorase histochemistry. Results Tyne …

Strain echocardiographic assessment of left atrial function predicts recurrence of atrial fibrillation

SI Sarvari, KH Haugaa, TM Stokke, HZ Ansari, IS Leren… – Eur Heart J Cardiovasc …, 2015

… Of these, 30 had not while 31 had recurrence of AF after radiofrequency ablation (RFA). Twenty

healthy individuals were included for comparison. … For patients with symptomatic drug-refractory

AF, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has become an important therapy option. …

[HTML] Current management of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

T Kanda, S Ogasawara, T Chiba, Y Haga, M Omata… – World J Hepatol, 2015

… of HCC. Many HCC patients are treated with surgical resection and radiofrequency

ablation (RFA), although these modalities should be considered in only selected

cases with a certain HCC number and size. Although there …

PP. 26.17: OUR CLINICAL EXPERIENCE WITH COMBINATION THERAPY OF OLMISARTAN AND AMLODIPINE IN THE TREATMENT OF RESISTANT …

T Chakalaa-Yancheva, S Tisheva, A Qnakieva… – Journal of Hypertension, 2015

… In all patients MRA excluded new or progression of pre- existing low grade renal artery stenosis

as well as focal aneurysms at the sites of radiofrequency ablation. In none of the patients new

segmental perfusion deficits in either kidney were detected on MRI. …

Multiscale Tetrahedral Meshes for FEM Simulations of Esophageal Injury

LA Neves, E Pavarino, MP Souza, CR Valencio… – Computer-Based Medical …, 2015

… [3] OJ Eick and D. Bierbaum, “Tissue temperature- controlled radiofrequency ablation,” Pacing

and clinical electrophysiology, vol. … [4] MO Siegel, DM Parenti, and GL Simon, “Atrialesophageal

fistula after atrial radiofrequency catheter ablation,” Clinical infectious diseases, vol. …

The meaning of gross tumor type in the aspects of cytokeratin 19 expression and resection margin in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

SC Gong, MY Cho, SW Lee, SH Kim, MY Kim, SK Baik – Journal of Gastroenterology …, 2015

… From March 2012 to December 2014, 87 patients with HCC underwent surgical treatment including

intraoperative radiofrequency ablation at Wonju Severance Christian Hospital, Wonju, Korea.

Among them, 75 patients who underwent only hepatectomy were enrolled in …

Impact of catheter ablation with remote magnetic navigation on procedural outcomes in patients with persistent and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation

Q Jin, S Pehrson, PK Jacobsen, X Chen – Journal of Interventional Cardiac …, 2015

… venous anatomy, left atrial (LA) volume, procedure time, mapping plus ablation time,

radiofrequency (RF) abla … CFAEs at the right atrium were not mapped and ablated in this study.

Although PVAI and CFAE ablation time were calculat- ed separately, CFAE ablation time did …

The role of AEG-1 in the development of liver cancer

CL Robertson, J Srivastava, D Rajasekaran, R Gredler… – Hepatic Oncology, 2015

… by rapid growth and early vascular invasion and thus the incidence and mortality of the disease

run in parallel [1,3]. Standard treatment options for patients afflicted with localized forms of the

disease include surgical resection, radiofrequency ablation or liver transplantation [4–7 …

Unexpected Findings in the Left Atrium of a Patient with a Paravalvular Mitral Leak

FS Silva, CA Barreiros, MC Antunes, ÂL Nobre – Journal of Cardiothoracic and …, 2015

… described including catheter-based cardiac interventions (eg valvular procedures, coronary

intervention, radiofrequency ablation), endocarditis, myocardial infarction and blunt cardiac

trauma.1 There are also cases of spontaneous dissection 2,10-11 occurring in patients with …

[PDF] Typical chest pain and precordial leads ST-elevation in patients with pacemakers-are we always looking at an acute myocardial infarction?

MM Ostojić, TS Potpara, MM Polovina, MM Ostojić… – Vojnosanitetski pregled, 2015

… ECG changes occurred due to pericardial re- action following two interventions: pacemaker

implantation a month before and radiofrequency catheter ablation of AV junction two weeks

before presentation in Emergency De- partment. Conclusion. …

[PDF] AB10-06

RC ABLATION – Heart Rhythm, 2015

Methods: The clinical features including freedom from AF/atrial tachycardia (AT) recurrence

as outcome after RFCA were compared between women and men in 1: 1 age, AF type,

duration of AF (±1 year) matched manner. Subgroup analysis was performed in categories …

MULTI-POLE SYNCHRONOUS PULMONARY ARTERY RADIOFREQUENCY ABLATION CATHETER

S Chen – US Patent 20,150,201,988, 2015

Abstract: A multi-pole synchronous pulmonary artery radiofrequency ablation catheter may

comprise a control handle, a catheter body and an annular ring. One end of the catheter

body may be flexible, and the flexible end of the catheter body may be connected to the …

Diagnostic and Interventional Endoscopy

Y Tomizawa, I Waxman – Atlas of Esophageal Surgery, 2015

… previous ablation zone. Ablation is repeated until the entire length of disease has

received radiofrequency energy (Fig. 3.15). After the entire lesion is ablated, the

guidewire, ablation catheter, and endoscope are removed. For focal …

[HTML] Osteoid osteoma masquerading tubercular arthritis or osteomyelitis on MRI: Case series and review of literature

JP Singh, S Srivastava, D Singh – Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging, 2015

… periostitis. The patient underwent CT-guided biopsy and radiofrequency ablation. The …

effusion. A CT-guided radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [Figure 10]C was performed and

the patient remained symptom-free at 20 months follow-up. Figure …

Hybrid Transthoracic Esophagectomy

B Borraez, MG Patti – Atlas of Esophageal Surgery, 2015

… hernia, 11, 12 Schatzki’s ring, 12, 13 sliding hiatal hernia, 10, 11, 46 squamous cell cancer, 19

Zenker’s diverticulum, 15, 97 Barrett’s esophagus esophagectomy, 151, 152 focal nodular lesion,

25, 27 proximal resection margin, 141, 147 radiofrequency ablation, 23, 29 salmon …

PP. 26.16: CAN AN HOSPITAL ADMISSION MODIFY THE COURSE OF PATIENTS WITH RESISTANT HYPERTENSION?.

J Ribeiro, A Correia, R Ferreira, P Morgado, JM Bastos… – Journal of Hypertension, 2015

… In all patients MRA excluded new or progression of pre- existing low grade renal artery stenosis

as well as focal aneurysms at the sites of radiofrequency ablation. In none of the patients new

segmental perfusion deficits in either kidney were detected on MRI. …

Perspectives on the modern management of non-valvularatrial fibrillation: non-valvular af

R Gopal, MH Tayebjee – SA Heart, 2015

… catheters and the development of balloon based or circular ablation catheters with multiple

ablation electrodes that can be applied to the pulmonary vein antrum to isolate pulmonary veins

and ablate left atrial substrate(44,17) (Figures 1 a,b,c). Both radiofrequency catheter and …

APPARATUS AND METHODS FOR CLOSING VESSELS

BB Hill, J Hong, W Qi – US Patent 20,150,201,947, 2015

… The following is a list of one or more advantages that may be achieved using the apparatus and

methods described herein, eg, as compared to endovenous laser, radiofrequency ablation

technologies, and other methods that destroy the vein by applying chemicals or applying …

Fluorescence Imaging Systems (PDE, HyperEye Medical System, and Prototypes in Japan)

T Ishizawa, N Kokudo – Fluorescence Imaging for Surgeons: Concepts and …, 2015

Hepatocellular Carcinoma Precursor Lesions

ML Smith – Surgical Pathology of Liver Tumors, 2015

Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS/RSD)

A scoring rule-based truthful demand response mechanism

K Hara, T Ito – Computer and Information Science (ICIS), 2015 IEEE/ …, 2015

… Therefore, conventional scoring rule with single item, such as Brier score [5] is of no use for this

mode. In order to rightfully incentivize the CA to make their prediction of device shifting for multiple

items rightfully; the continuous ranked probability score (CRPS) is applied [13]. …

[PDF] Why Attackers Win: On the Learnability of XOR Arbiter PUFs

F Ganji, S Tajik, JP Seifert – 2015

… These attacks, as cost-effective approaches, can clone the challenge-response behavior of an

arbiter PUF by collecting a subset of challenge-response pairs (CRPs). … Moreover, when applying

current ML attacks, the maximum number of CRPs required for Page 3. …

[PDF] A Multivariate Modeling Approach for Generating Ensemble Climatology Forcing for Hydrologic Applications

S Khajehei – 2015

Page 1. Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses

Spring 7-21-2015 A Multivariate Modeling Approach for Generating Ensemble Climatology Forcing

for Hydrologic Applications Sepideh Khajehei Portland State University …

[HTML] Oil Palm Leaf and Corn Stalk–Mechanical Properties and Surface Characterization

Z Daud, MZM Hatta, H Awang – Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2015

… Bhaduri et al., 1995; BK Bhaduri, A. Day, SB Mondal, .SK Sen; Ramie hemicelluloses as beater

additive in a paper making from jute-stick kraft pulp. Industrial Crps and Products, 4 (1995), pp.

79–84. Daud et al., 2013; Z. Daud, MZM Hatta, ASM Kassim, AM Aripin, H. Awang; …

[HTML] Nerve injury and neuropathic pain–a question of age

M Fitzgerald, R McKelvey – Experimental Neurology, 2015

… Furthermore several complex pain syndromes (eg CRPS) that emerge in older children are

associated with little or no measurable disease activity or inflammation at the time of presentation

and are clinically defined as ‘functional’ or ‘medically unexplained’ (Bromberg et al …

Acute acalculous cholecystitis and cardiovascular disease: a land of confusion

M Tana, C Tana, G Cocco, G Iannetti, M Romano… – Journal of Ultrasound, 2015

… Most common clinical onset was represented by fever (70 %) in opposite to abdominal pain

which occurred in 20 % of patients. 8/10 patients were male. Elevated CRPs, leukocytosis

(60 %), and elevated aminotransferase (30 %) occurred frequently. …

[PDF] Characterizing the Stability of Okun’s Law during Economic Recessions by cross-Recurrence Plot and Rolling Regression

J Gao, Y Cao

… 2 n xx x , , , and 1 2 n yy y , , , , which, for concreteness, may be equated to unemployment and

production data, one obtains CRPs (Marwan & Kurths 2002; Marwan, et al. 2007). … 4, No. 3 ~ 5 ~

Figure 2. Cross recurrence plots (CRPs); notice the correspondence of vertical …

[PDF] Use of Hidden Markov Mobility Model for Location Prediction and Biclustering for Cache Replacement in MANET

BD Shelar, MDK Chitre

… But these policies give satisfactory performance for stable user and prove inefficient for mobile

user which free to change his direction. Direction and Distance Based CRPs think for the mobile

nature of user. … Prediction Based CRPs analyze the history of users’ movements. …

Field Deployable Chemical Redox Probe for Quantitative Characterization of Carboxymethylcellulose Modified Nano Zerovalent Iron

D Fan, S Chen, RL Johnson, PG Tratnyek – 2015

Page 1. 1 2 Field Deployable Chemical Redox Probe for Quantitative Characterization of 3

Carboxymethylcellulose Modified Nano Zerovalent Iron 4 5 6 Dimin Fan, Shengwen Chen, Richard

L. Johnson, and Paul G. Tratnyek* 7 8 Institute of Environmental Health 9 …

Technical innovations for small-scale producers and households to process wet cassava peels into high quality animal feed ingredients and aflasafe™ substrate

I Okike, A Samireddypalle, L Kaptoge, C Fauquet… – Food Chain, 2015

Headache and Pain

R Baron, A May – 2015

Molecular Biology of Retinoblastoma

SD Walter, JW Harbour – Recent Advances in Retinoblastoma Treatment, 2015

… Rb directly inhibits E2Fs by binding and masking the transactivation domain, and it also recruits

chromatin remodeling proteins (CRPs) that alter local chromatin structure into a confirmation

that is not permis- sive for transcription.(b) When Rb is hyperphosphory- lated, it does …

[PDF] Guidelines for Neuromusculoskeletal Infrared Thermography Sympathetic Skin Response (SSR) Studies

DO Getson, S Govindan, J Uricchio, T Bernton…

… Assessment of patients with presumptive Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) Type I or

II – formally known as Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (RSD), Thoracic Outlet Syndrome,

Vaso-motor Headache and Barre’-Leiou Syndrome. … CRPS: Current Diagnosis and Therapy. …

[HTML] Thread: Advances in treatment of post-amputation phantom limb pain

W Young, J Date

… reviewed fifteen papers reporting mirror therapy to treat upper limb function and concluded that

most of the studies were weak methodologically and that the results suggest possible benefit

in patients after stroke and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) but the …

[PDF] Guidelines For Dental-Oral And Systemic Health Infrared Thermography

M Brioschi, H Usuki, BSN Jan Crawford, P Steed…

… c. Relevant risk factors for inflammation or vasomotor instability: prior history of RSD

or CRPS, trauma, fracture, repetitive use, vibration syndrome, peripheral neuropathy,

spinal pathology, radiculopathy, vasomotor headache, Page 4. …

[HTML] Chronic Pain Medication & Treatment Guide

AR Guide

… cord injuries. It may develop months or years after injury or damage to the CNS.

This also includes conditions such as chronic headaches, fibromyalgia, and Complex

Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS). Tailoring selection of …

[DOC] WORKSHOP ON BEST PRACTICE METHODS FOR ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF POLICY ORIENTED RESEARCH SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR …

F Place, P Hazell

WORKSHOP ON BEST PRACTICE METHODS FOR ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF

POLICY ORIENTED RESEARCH. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR

THE CGIAR. Frank Place and Peter Hazell. WORKSHOP ON …

CRPS A contingent hypothesis with prostaglandins as crucial conversion factor

PHE van der Veen – Medical Hypotheses, 2015

Abstract CRPS is an acute pain disease expressed as chronic pain with a severe loss of

tissue and function. CRPS usually occurs after minor injuries and then progresses in a way

that is scarcely controllable, or completely uncontrollable. This article addresses the …

Vitamin C to Prevent Complex Regional Pain Syndrome in Patients With Distal Radius Fractures: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials

N Evaniew, C McCarthy, YV Kleinlugtenbelt, M Ghert… – Journal of orthopaedic …, 2015

… Collapse Box Abstract. Objective: To determine whether vitamin C is effective in preventing

complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) in patients with distal radius fractures. … 2 CRPS has been

previously referred to as causalgia, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and algodystrophy. 3. …

Injury of the corticoreticular pathway in patients with mild traumatic brain injury: A diffusion tensor tractography study

HD Lee, SH Jang – Brain Injury, 2015

… Figure 1. Diffusion tensor tractography for the corticoreticular pathway (CRP): a normal control

subject (44 year-old, female), type A = the CRPs showed narrowing, although integrity was

preserved from the premotor cortex to the reticular formation of the medulla, type B = the …

[PDF] Plasma Exchange Therapy in Patients with Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

E Aradillas, RJ Schwartzman, JR Grothusen, A Goebel – Pain Physician, 2015

Page 1. Background: Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a severe chronic

pain condition that most often develops following trauma. … These patients were then

placed on Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a …

Controversial Pain Syndromes of the Arm: Pathogenesis and Surgical Treatment of Resistant Cases

A Wilhelm – 2015

[PDF] Mixture EMOS model for calibrating ensemble forecasts of wind speed

S Baran, S Lerch – arXiv preprint arXiv:1507.06517, 2015

… The most popular scoring rules are the logarithmic score, that is the negative logarithm of the

predictive PDF evaluated at the verifying observation and the continuous ranked probability score

(CRPS; Gneiting and Raftery, 2007; Wilks, 2011). … CRPS(F, x) := ∫ ∞ …

[PDF] Targeted Ultrasound-Guided Double Catheters (Infraclavicular-Brachial Plexus, Median Nerve) Facilitate Hand Rehabilitation with Superb Analgesia and Motor …

AE Holman, B Sharma, VE Modest – Open Journal of Anesthesiology, 2015

… http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract A 44-year-old male who suffered a

crush-degloving hand injury complicated by Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) type

I was scheduled for operative hand manipulation and inpatient physi- otherapy. …

Leads for neurostimulation and methods of assembling same

A Raines – US Patent 9,084,882, 2015

… As used herein the term “complex regional pain syndrome” or “CRPS” refers to painful

conditions that usually affect the distal part of an upper or lower extremity and are

associated with characteristic clinical phenomena. CRPS …

[PDF] Identification and characterization of a novel family of cysteine-rich peptides (MgCRP-I) from Mytilus galloprovincialis

M Gerdol, N Puillandre, G De Moro, C Guarnaccia… – Genome Biology and …, 2015

… encoding peptides with unique chemico-physical properties and/or sequence patterns. Actually,

cysteine-rich peptides (CRPs) encompass a large and widespread group of secreted … plants

(Gruber, et al. 2007; Marshall, et al. 2011; Taylor, et al. 2008). Invertebrate CRPs are …

Peri‐infarct reorganization of an injured corticoreticulospinal tract in a patient with cerebral infarct

SH Jang, J Lee, HD Lee – International Journal of Stroke, 2015

… (c) The CRPs are descended through the subcortical white matter in two age-matched normal

control subjects. Letter to the editor © 2015 World Stroke Organization E62 Vol 10, August 2015,

E62–E63 Page 2. References 1 Yeo SS, Chang MC, Kwon YH, Jung YJ, Jang SH. …

Fibromyalgia

Depressive-like symptoms in a reserpine-induced model of fibromyalgia in rats

A Blasco-Serra, F Escrihuela-Vidal, EM González-Soler… – Physiology & Behavior, 2015

Abstract Since the pathogenesis of fibromyalgia is unknown, treatment options are limited,

ineffective and in fact based on symptom relief. A recently proposed rat model of

fibromyalgia is based on central depletion of monamines caused by reserpine …

Is there any link between joint hypermobility and mitral valve prolapse in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome?

E Kozanoglu, IC Benlidayi, RE Akilli, A Tasal – Clinical Rheumatology, 2015

Abstract The objective of the present study is to determine whether benign joint

hypermobility syndrome (BJHS) modifies the risk of mitral valve prolapse (MVP) in patients

with fibromyalgia (FM). Female patients fulfilling the 1990 American College of …

[HTML] Calibration and Validation of the Dutch-Flemish PROMIS Pain Interference Item Bank in Patients with Chronic Pain

MHP Crins, LD Roorda, N Smits, HCW de Vet… – PLOS ONE, 2015

… as pain that persists beyond the normal tissue healing time, in which the most prevalent pain

is musculoskeletal pain, with prevalence varying from 30–40% for low back pain, 15–20% for

shoulder- and neck pain, 10–15% for chronic widespread pain and 2% for fibromyalgia [3,4 …

Assessment of response bias in neurocognitive evaluations

DA Carone – NeuroRehabilitation, 2015

… survey data of neuropsychologists show that the base rates of malingering or symptom

exaggeration are much higher (29% to 41%) in settings where patients are seeking financial

compensation or disability and in patient groups (ie, concussion, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue …

[PDF] SENSE OF WELL-BEING IN PATIENTS WITH FIBROMYALGIA. AEROBIC EXERCISE PROGRAM IN A MATURE FOREST: A PILOT STUDY

S Lopez-Pousa, GB Pagès, S Monserrat-Vila

ABSTRACT Background and objective: Most patients with fibromyalgia benefit from different

forms of physical exercise. Studies show that exercise can help restore the body’s

neurochemical balance and that it triggers a positive emotional state. So, regular exercise …

[HTML] Miller Chiropractic & Laser Treatment Center

D Emery

… Acta Medica Academica 2013;42(1):46-54. doi: 10.5644/ama2006-124.70. Study Finds

Chiropractic Beneficial for Fibromyalgia. A new study from Egypt reports that chiropractic care

can be an effective treatment strategy for fibromyalgia treatment with chiropractic care. …

[PDF] Cost-effectiveness of 40-hour versus 100-hour vocational rehabilitation on work participation for workers on sick leave due to subacute or chronic musculoskeletal …

TT Beemster, JM van Velzen, CAM van Bennekom… – Trials, 2015

… as follows: 1) individuals of working age (18 to 65 years); 2) suffering from subacute (6 to 12 weeks)

or chronic (>12 weeks) nonspecific musculoskeletal pain such as back, neck, shoulder,

widespread pain, Whiplash Associated Disorder (WAD I or II), or fibromyalgia; 3) having …

Peer-Reviewed Abstracts

D Avans – Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 2015

… Fine motor control knowingly declines with age and certain diseases such as fibromyalgia and

cerebral palsy (Perez-de-Heredia-Torres, 2013). … Research of this nature could also be translated

to diseased populations such as those with fibromyalgia or diabetes. …

Gastro-protective and Anti-stress Efficacies of Monomethyl Fumarate and a Fumaria indica Extract in Chronically Stressed Rats

A Shakya, UK Soni, G Rai, SS Chatterjee, V Kumar – Cellular and Molecular …, 2015

… are some of the major symptoms of numerous, if not all, chronic inflammatory diseases

accompanying central sensitivity syndromes (Yunus 2008 ), and it is now well recognized that

cytokine and immune system abnormalities are the root cause of fibromyalgia and other central …

[PDF] Mechanisms of action of balneotherapy in rheumatic diseases

A Fioravanti, S Cheleschi – IV CIBAP BOÍ 2015

… Anti-inflammatory aspects Recent studies have shown a reduction of circulating levels of

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and Leukotriene B4 (LTB4), important mediators of inflammation and

pain, in patients suffering from OA or fibromyalgia who undergo mud-packs or …

Determinants of Patient Satisfaction in an Academic Rheumatology Practice.

JH Ku, A Danve, H Pang, D Choi, JT Rosenbaum – Journal of clinical rheumatology: …, 2015

… 95% CI, -15.25 to -3.25), arthralgia (β = -8.67; 95% CI, -16.60 to -0.74), myalgia (β = -8.67; 95%

CI, -16.60 to -0.74), gout (β = -7.5; 95% CI, -14.13 to -0.89), ankylosing spondylitis (β = -5.20;

95% CI, -9.65 to -0.75), pain (β = -4.62; 95% CI, -8.43 to -0.81), fibromyalgia (β = -4.62; 95 …

Method and Apparatus for Diagnosing and Assessing Centralized Pain

JB Hargrove – US Patent 20,150,201,879, 2015

… Because of this emerging understanding, the role of CS is increasingly being shown to be

pathological in seemingly unrelated chronic pain conditions and syndromes including fibromyalgia,

complex regional pain syndrome, phantom pain, and migraine headaches. …

FATTY ACID DERIVATIVES FOR USE IN A METHOD OF TREATING DEPRESSION AND ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS

E Berry, Y Avraham, J Katzhendler, J Mograbi… – US Patent 20,150,202,179, 2015

… Abstract: The invention provides fatty acid derivatives for use in a method of treatment of at least

one disease, disorder or condition selected from anxiety, depression, conditions associated

menopause, stress, bipolar disorder, neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. …

ANTIBODIES TO IL-6 AND THEIR USES

A Rajpal, MN Devalaraja, K Toy, L Yang, H Huang… – US Patent 20,150,203,574, 2015

… The term “fibromyalgia” is also known as fibromyalgia syndrome. The American College

of Rheumatology (ACR) 1990 classification criteria for fibromyalgia include a history

of chronic, widespread pain for more than three months …

Impact of Gender-Based Aggression on Women’s Mental Health in Portugal

M Reis, L Ramiro, MG de Matos – … Mental Health: Resistance and Resilience in …, 2015

… The rate was even higher for women who had experienced non-partner sexual violence (WHO,

2013). Health effects can also include headaches, back pain, abdominal pain, fibromyalgia,

gastrointestinal disorders, limited mobility, and poor overall health (WHO, 2013). …

Pain 2014 Refresher Courses: 15th World Congress on Pain

SN Raja, CL Sommer – 2015

Restless Legs Syndrome: The Devil Is in the Details

PJ Sampognaro, RE Salas, A Kalloo, C Gamaldo – Sleepy or Sleepless: Clinical …, 2015

… medical conditions Restless legs syndrome (Willis-Ekbom disease) Renal failure Periodic limb

movement disorder Anemia REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) Peripheral neuropathy

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) Rheumatoid arthritis Fibromyalgia Attention deficit …

[PDF] Dermatologic Extrahepatic Manifestations of Hepatitis C

B Dedania, GY Wu – Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology, 2015

… cutanea tarda23 – Lichen planus33,35,36 – Sicca syndrome – Auto-antibody productions

(rheumatoid factor, cryoglobulins, anti-smooth muscle) – Glomerulonephritis12 C. Possible

association2,16 – Polyarthritis – Pruritus – Fibromyalgia – Chronic polyradiculoneuropathy – Lung …

PHOSPHATIDYLINOSITOL-3-KINASE C2 BETA MODULATORS AND METHODS OF USE THEREOF

E Skolnik, Z Li, S Srivastava – US Patent 20,150,204,846, 2015

… Exemplary IgE-mediated allergic disorders include, without limitation, allergic rhinitis,

allergic or atopic asthma, anaphylaxis, atopic dermatitis, eczema, hay fever,

fibromyalgia, and an immediate type hypersensitivity reaction. …

Psychological Interventions for the Management of Chronic Pain: a Review of Current Evidence

RS Kaiser, M Mooreville, K Kannan – Current Pain and Headache Reports, 2015

… A few of the many variants of this approach will be highlighted. Currently, cognitive

behavioral therapy (CBT) is a first-line psychological treatment for individuals with chronic

pain, such as back pain, headache, arthritis, and fibromyalgia [ 12 •]. …

by admin | Jul 17, 2015 | Uncategorized

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a chronic, predominantly neuropathic and partly musculoskeletal pain disorder often associated with autonomic disturbances. It is divided into 2 types, reflecting the absence or presence of a nerve injury.

Patients with either type may exhibit symptoms such as burning pain, hyperalgesia, and/or allodynia with an element of musculoskeletal pain. CRPS can be distinguished from other types of neuropathic pain by the presence of regional spread as opposed to a pattern more consistent with neuralgia or peripheral neuropathy. Autonomic dysfunction (such as altered sweating, changes in skin color, or changes in skin temperature); trophic changes to the skin, hair, and nails; and altered motor function (such as weakness, muscle atrophy, decreased range of motion, paralysis, tremor, or spasticity) also can be present.1,2

At least 50,000 new cases of CRPS are diagnosed in the United States annually.1 Although the incidence rate is subject to debate, a large epidemiologic study from The Netherlands involving 600,000 patients suggests an incidence of 26.2 per 100,000 individuals. The study also found that women are 3 times more likely to be affected, with postmenopausal women having the greatest risk.3

Presentation

Type 1 CRPS, formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy, often is triggered by a minor or major trauma—fractures account for about 60% of cases.2 Surgery is the next most common precipitating event at 20%. Other etiologies include injections, venipuncture, infections, burns, cerebrovascular accidents, or myocardial infarctions.2,4 There are no identifiable precipitating events in about 10% of patients.2

Type 2, formerly known as causalgia, often is related to high-velocity, blunt injuries, which make up more than 75% of cases. But any process that results in nerve injury, such as surgery, fractures, or injections, also can cause type 2 CRPS.4,5 More than 50% of type 2 cases involving the upper extremities often are related to injuries of the median nerve alone or in combination with another nerve of the upper extremity.5 About 60% of cases in the lower extremities are related to injury of the sciatic nerve.5 Almost all cases involve only partial nerve transection, with upper extremity involvement more prevalent than lower extremity.

Pathophysiology

Historically, CRPS has been poorly understood, and a lack of consistent diagnostic criteria often has been cited in literature. But research in recent years has provided substantial insight into the pathophysiology of the disorder.

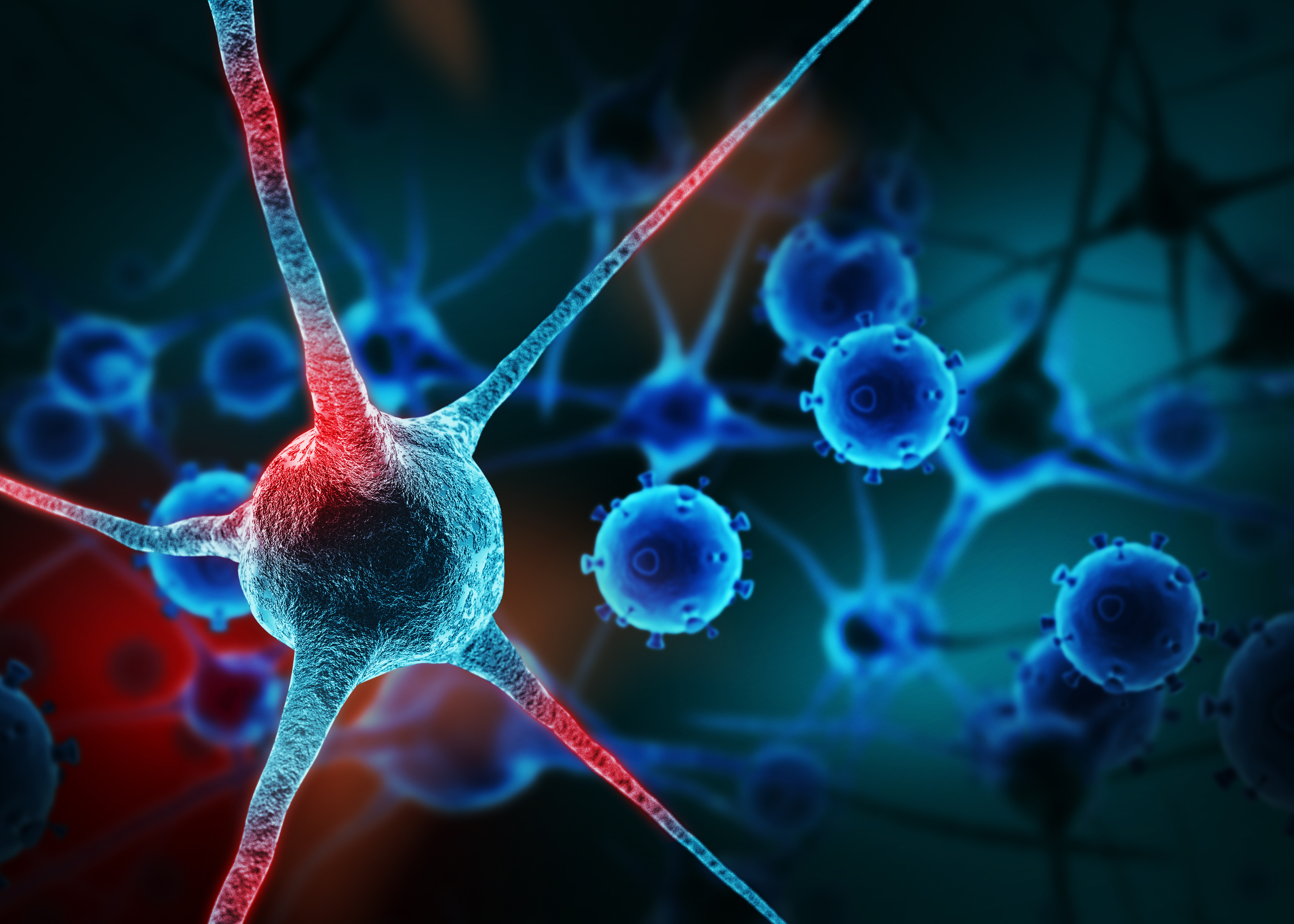

As with many other complex conditions, the mechanisms involved in CRPS are multifactorial (Table 1) and include the peripheral and central nervous systems (Figure 1).1 Factors such as altered sympathetic and catecholaminergic function, peripheral and central sensitization, peripheral and central neurogenic inflammation, altered somatosensory representation in the brain, genetics, and psychology all affect patients to varying degrees.

| Table 1. Summary of Pathophysiologic Mechanisms That May Contribute to CRPS1 |

| Altered cutaneous innervation |

- Density of C- and Aδ-fibers in CRPS-affected region

- Altered innervation of hair follicle and sweat glands in CRPS-affected limb

|

| Central sensitization |

- Increased windup in CRPS patients

|

| Peripheral sensitization |

- Local hyperalgesia in CRPS-affected vs unaffected extremity

- Increased mediators of peripheral sensitization

|

| Altered SNS function |

- Bilateral reductions in SNS vasoconstrictive function predict CRPS occurrence prospectively

- Vasoconstriction to cold challenge is absent in acute CRPS but exaggerated in chronic CRPS

- Sympatho-afferent coupling

|

| Circulating catecholamines |

- Lower norepinephrine levels in CRPS-affected vs unaffected limb

- Exaggerated catecholamine responsiveness because of receptor up-regulation related to reduced SNS outflow

|

| Inflammatory factors |

- Increased local, systematic, and cerebrospinal fluid levels of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β, -2, and -6

- Decreased systemic levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10)

- Increased systemic levels of proinflammatory neuropeptides, including CGRP, bradykinin, and substance

- Animal postfracture model of CRPS-1 indicates that substance P and TNF-α contribute to key CRPS features

|

| Brain plasticity |

- Reduced representation of the CRPS-affected limb in somatosensory cortex

- These alterations are associated with greater pain intensity and hyperalgesia, impaired tactile discrimination, and perception of sensations outside of the nerve distribution

|

| Genetic factors |

- In the largest CRPS genetic study to date (150 CRPS patients), previously reported associations were confirmed between CRPS and HLA-related alleles

- A TNF-α promoter gene polymorphism is associated with “warm CRPS”

|

| Psychological factors |

- Greater preoperative anxiety prospectively predicts CRPS symptomatology after total knee arthroplasty

- Emotional arousal has a greater effect on pain intensity in CRPS than in non-CRPS chronic pain, possibly via associations with catecholamine release

|

| CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide; CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome; IL, interleukin; SNS, sympathetic nervous system; TNF, tumor necrosis factor |

|

Figure 1. Speculative model of interacting CRPS mechanisms.

CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide; CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor

Central Sensitization

Central sensitization is an increased firing of nociceptive fibers in response to intense or persistent noxious stimuli. It is mediated by the nociception-induced release of neuropeptides such as bradykinin, glutamate, and substance P. This phenomenon is part of the reason patients experience allodynia and hyperalgesia. It is not known whether central sensitization precedes, occurs with, or follows development of other CRPS signs and symptoms.1,4,6

Peripheral Sensitization

Peripheral sensitization occurs when an initial tissue trauma causes proinflammatory neuropeptides to be released from primary afferent fibers. These neuropeptides increase background firing of nociceptors, decrease the firing threshold for thermal and mechanical stimuli, and increase firing in response to nociceptive stimuli. This decrease in firing threshold contributes to patients experiencing allodynia and hyperalgesia.1,4,6

Sympathetic Nervous System

Several human studies demonstrated expression of adrenergic receptors on nociceptive fibers after nerve injury. Given that there is likely some sort of nerve damage in type 1 CRPS, this explains why sympathetic outflow has an important effect on pain in patients with this condition. Manipulations with whole-body cooling and heating have supported the theory of sympatho-afferent coupling, although it would not be correct to imply that altered sympathetic function is solely responsible for the development of CRPS. Vascular abnormalities seen in CRPS also are mediated by altered levels of endothelin-1, nitric oxide synthase, nitric oxide, and impaired endothelial-related vasodilatory function. During the progression from acute to chronic CRPS, patients have intense vasoconstriction response in the setting of lowered levels of norepinephrine, implying altered local sympathetic outflow. This is believed to occur due to up-regulation of noradrenergic receptors as a response to low levels of catecholamines. When patients experience pain or regular life stress, these sensitive receptors respond intensely to the release of catecholamines, resulting in a cold, blue, and sweaty appearance.1

Inflammation

The inflammatory process is involved in at least the acute phase of CRPS. There are 2 potential sources of inflammation:

- Classic mechanisms through actions of immune cells, which, after tissue trauma, secrete proinflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1, -2, and -6, and tumor necrosis factor-α.

- Neurogenic inflammation, which occurs through the release of proinflammatory mediators directly from injured nociceptive fibers in response to various stimuli. These neuropeptides include substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, and bradykinin, which promotes plasma extravasation and local tissue edema.1

A subset of patients with CRPS has been found to have low levels of anti-inflammatory and high levels of proinflammatory cytokines.4

Autoimmunity

It has been suggested that autoantibodies may play a role in CRPS. Autoantibodies found in the plasma of patients with CRPS are active at the muscarinic cholinergic and β2 adrenoceptors. Transfer of serum immunoglobulin G to mice from patients with CRPS elicited symptoms of CRPS in recipient mice.7

Genetics

Although there is no clear evidence of genetic predisposition to developing CRPS, it would be prudent to further investigate genetic factors that influence inflammatory and other mechanisms contributing to the syndrome. The largest study of 150 CRPS patients has found a link between CRPS and HLA-related alleles.1,4

Psychological Factors

To date, no evidence has suggested a purely psychological form of CRPS. However, poor coping and emotional stress can certainly raise levels of circulating catecholamines, which could exacerbate vasomotor signs of CRPS, cause pain, and maintain central sensitization.1,4

Brain Plasticity

Functional magnetic resonance imaging scans have shown that there is significant cortical reorganization of somatosensory cortex, which may underlie various manifestations of CRPS. Functional disturbances in posterior parietal cortex responsible for integrating various external stimuli and constructing real-time body schema in space, also may contribute to chronification of pain.1,4,7

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CRPS is clinical and depends on patient history, physical examination, and findings of musculoskeletal degeneration and secondary pain that develops as a result of persistence of the disease state. CRPS is a diagnosis of exclusion and cannot be made in the presence of other diagnoses that can be responsible for the presentation. Chronic CRPS needs to have symptoms and signs consistent with time-dependent effect of CRPS (ie, atrophy, dystrophy, contractions, and secondary pain).

In the initial several months of CRPS, hypoesthesia and hyperalgesia are common, whereas ongoing disease anesthesia dolorosa can be seen.2 The pain present in later cases when compared with the acute phase is more often present at rest and resistant to treatment. One of the hallmarks of persistent CRPS is the accumulation of orthopedic and neuropathic findings due to altered biomechanics of the affected area and tissue dystrophy and atrophy in superficial and deeper tissues, as well as development of secondary pain in the contralateral limb and other parts of the body as the patient attempts to compensate.

A main reason why CRPS is difficult to diagnose and treat is because the majority of patients do not have classic “warm” (acute) or “cold” (cold) affected limbs—they fall somewhere along the spectrum.1,4 Veldman et al described more patients as having the “cold” type as the duration of CRPS increases, however, some patients with CRPS for more than 10 years still have “warm” limbs.2 And despite being classified as 2 types, there is no evidence that pathophysiologic mechanisms or treatment responsiveness differ in any appreciable way except that type 2 and underlying nerve injury may need to be addressed directly, sometimes surgically (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of treatment modalities based on pathophysiologic mechanisms.7

Skin biopsies of patients with type I CRPS show a significantly decreased amount of C and Aδ-fibers after tissue injury, possibly indicating nerve damage may be present in type 1.1 However, there is no clear evidence as to whether this is a cause or effect of CRPS. Animal models support an increased nociceptive firing in response to norepinephrine, providing evidence that there is sympatho-afferent coupling, which has been suggested by human studies.1 There is further suggestion in animal models that a transcription factor, nuclear factor-β, could play a role in CRPS. This may provide an upstream link between increased proinflammatory neuropeptides and increased proinflammatory cytokines in CRPS.1,4

It also has been shown that patients with CRPS and people with prolonged immobilization, from things like casts for limb fractures, show similar signs of edema, skin color changes, limited range of motion, and altered sensation. This suggests that patients with CRPS experience derangement of normal physiologic responses, making it difficult to identify when these physiologic changes becomes pathologic CRPS and not another diagnosis.4

Diagnostic Tools

During a consensus workshop in 1994, the International Association for Study of Pain (IASP) proposed diagnostic criteria based on clinical symptomatology (Table 2).8 Criticisms of the IASP criteria included a lack of specificity and misdiagnosing other types of neuropathic pain conditions as CRPS. The false diagnosis was thought to stem from the IASP criteria being met solely by self-reported symptoms uncovered by the history without physical signs and symptoms.7

| Table 2. IASP CRPS Diagnostic Criteria8 |

2-4 of the following with 2, 3, and 4 being mandatory:

- The presence of an initiating noxious event, or a cause of immobilization.

- Continuing pain, allodynia, or hyperalgesia with which the pain is disproportionate to any inciting event.

- Evidence at some time of edema, changes in skin blood flow, or abnormal sudomotor activity in the region of the pain.

- This diagnosis is excluded by the existence of conditions that would otherwise account for the degree of pain and dysfunction.

|

All of the following:

- The presence of continuing pain, allodynia, or hyperalgesia after a nerve injury, not necessarily limited to the distribution of the injured nerve.

- Evidence at some time of edema, changes in skin blood flow, or abnormal sudomotor activity in the region of the pain.

- This diagnosis is excluded by the existence of conditions that would otherwise account for the degree of pain and dysfunction.

|

| CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome; IASP, International Association for the Study of Pain |

|

In an aim to improve the IASP criteria, an international consensus meeting was held in Budapest in 2003. The results were based on the previously published Harden/Bruehl criteria (Table 3).9 A 2010 study showed the IASP criteria of being 100% sensitive but only 41% specific in 113 CRPS type 1 patients and 47 non-CRPS neuropathic pain patients. The new Budapest criteria revealed 99% sensitivity with 68% specificity.10 Veldman’s criteria includes physical signs in combination with symptoms and was derived from a cross-sectional cohort study of 829 patients (Table 4).2

| Table 3. Harden/Bruehl CRPS Diagnostic Criteria9 |

- Continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event

- Must report ≤1 symptom in 3 of the following 4 categories:

- Sensory:

Reports of hyperesthesia and/or allodynia

- Vasomotor:

Reports of temperature asymmetry and/or skin color changes and/or skin color asymmetry

- Sudomotor/Edema:

Reports of edema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/Trophic:

Reports of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nails, skin)

- Must display ≤1 sign at time of evaluation in ≥2 of the following categories:

- Sensory:

Evidence of hyperalgesia (to pinprick) and/or allodynia (to light touch and/or temperature sensation and/or deep somatic pressure and/or joint movement)

- Vasomotor:

Evidence of temperature asymmetry (>1∞C) and/or skin color changes and/or asymmetry

- Sudomotor/Edema:

Evidence of edema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/Trophic:

Evidence of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nails, skin)

- There is no other diagnosis that better explains the signs and symptoms

|

| Same as CRPS I but with the evidence of a peripheral or central nerve injury |

| Patients who do not fully meet the clinical criteria, but whose signs and symptoms cannot be better explained by another diagnosis |

| CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome; NOS, not otherwise specified |

|

| Table 4. Veldman2 CRPS Diagnostic Criteria |

- Presence of 4 or 5 of the following:

- Unexplained diffuse pain

- Difference in skin color relative to other limb

- Diffuse edema

- Difference in skin temperature relative to other limb

- Limited active range of motion

- Occurrence or increase of above signs and symptoms after use.

- Above signs and symptoms are present in an area larger than the area of primary injury or operation and include the area distal to the primary injury.

|

|

| CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome |

|

Treatment

Although the majority of CRPS symptoms resolve within an approximate 12-month period, an estimated 25% of patients still fulfill IASP diagnostic criteria at 12 months and may suffer from CRPS chronicity. CRPS following fracture has a better resolution rate; “cold” CRPS or upper-limb involvement has the worst outcome. Because CRPS is a multifactorial disease with poorly understood mechanisms, the mainstay of treatment remains physical and occupational therapy aimed at return and preservation of function, prevention of loss of range of motion, and prevention of contractures and atrophy.4

Pharmacologic Treatment

IV Ketamine has proven to be very effective in the treatment of CRPS /RSD

At the Florida Spine Institute, treatment protocols are individually planned depending on the nature of pain and the patient’s responsiveness to initial sessions. Infusion cocktails are prepared in house so that they can be tailored to each patient’s therapeutic needs. A variety of medications are often used:

- Lidocaine

- Ketamine

- Bisphophonates

- Magenesium

These medications are typically mixed with saline in an IV bag and infused slowly over several hours, depending on the medication and/or protocol being used. Usually, a series of treatments will be recommended daily for a period of a week or more. The duration of pain relief following one or more ketamine infusions cannot be predicted. The goal is to achieve lasting relief as measured in weeks or months following the last treatment. Most patients who enjoy prolonged pain relief will need to return on occasion for a booster infusion, or continue to take low dose intranasal ketamine at home.

There is also convincing results with regard to IV bisphosphonates—most recently neridronate in patients with disease duration of less than 6 months. At 1-year follow-up, neridronate showed improved pain control. Multiple neuropathic medications such as gabapentin, tricyclic antidepressants, and opioids have been used through their extrapolated benefit in neuropathic conditions other than CRPS. Oral steroids continue to be used in acute CRPS, although the evidence is poor and sympatholytic drugs are used by clinicians with low success rates.7,11,12 But a recent small trial using low-dose oral phenoxybenzamine showed significant functional improvement in patients with CRPS.13 Taking everything above into consideration, we can conclude that the majority of pharmacologic treatments used by clinicians are quite empirical and largely based on personal preferences and experiences.

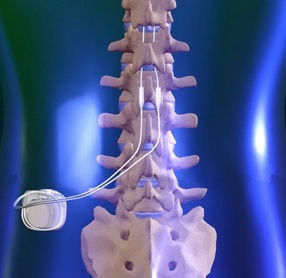

Interventional and Surgical Techniques

The main utility of interventional pain medicine in CRPS is to enable proper physical or occupational therapy and break the cycle of peripheral and/or central pain. Moderate evidence shows that sympathetic blockade is effective. Spinal cord stimulators appear to provide significant improvement of function in type 1 CRPS, and are more cost-effective over a patient’s lifetime compared with physical therapy and medical management.4,14 Although there is great resistance to surgery for CRPS patients, significant pain resolution may be achieved through nerve decompression or denervation procedures, neuroma resection, and neurolysis once patients are properly identified by nerve blocks. In many patients, the noxious stimulus is maintained through nerve compression; osteophytes; fibrosis; neuroma; arteriovenous malformation; or anything that entraps, compresses, or distorts the nerve. Surgery may be indicated in these cases.

Psychological Interventions

Psychological factors play a role in the treatment of CRPS. There is likely benefit in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Correcting body image also may help in CRPS affected patients.4,7

References

- Bruehl S. An update on the pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(3):713-725.

- Veldman PH, Reynen HM, Arntz IE, et al. Signs and symptoms of reflex sympathetic dystrophy: prospective study of 829 patients. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1012-1016.

- de Mos M, de Bruijn AGJ, Huygen FJPM, et al. The incidence of complex regional pain syndrome: a population-based study. Pain. 2007;129(1-2):12–20.

- Borchers AT, Gershwin ME. Complex regional pain syndrome: a comprehensive and critical review. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(3):242-265.

- Hassantash SA, Afrakhteh M, Maier RV. Causalgia: a meta-analysis of the literature. Arch Surg. 2003;138(11):1226-1231.

- Rockett, M. Diagnosis, mechanisms and treatment of complex regional pain syndrome. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014; 27(5):494-500.

- Gierthmühlen J, Binder A, Baron R. Mechanism-based treatment in complex regional pain syndromes. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(9):518-528.

- Merskey M, Bogduk N, eds. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definition of pain terms; second edition. Seattle: WA; 1994.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanton-Hicks M, et al. Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med. 2007;8(4):326-331.

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RS, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the “Budapest Criteria”) for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2010; 150(2):268-274.

- Rowbotham, MC. Pharmacologic management of complex regional pain syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2006:22(5):425-429.

- O’Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, et al. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD009416.

- Inchiosa MA Jr. Phenoxybenzamine in complex regional pain syndrome: potential role and novel mechanisms. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2013;2013:978615.

- Taylor RS, Van Buyten JP, Buchser E. Spinal cord stimulation for complex regional pain syndrome: a systematic review of the clinical and cost-effectiveness literature and assessment of prognostic factors. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(2):91-101.